Matrix Files

Where You Have Taken The Red Pill

Coin's Financial Course - Chapter IV - THE FOURTH DAY.

« Chapter III PDF File found here Chapter V »

CHAPTER IV.

The comments of the morning papers on the third day's session of the school on the whole were favorable. The published accounts had been full and substantially correct, and the Times and Inter Ocean reproduced the illustrations that had been used.

In this way the proceedings of the school had been laid before thousands of readers, whose interest had been aroused, and long before 10 o'clock the hall was crowded, and standing room could not be had.

The Inter Ocean in an editorial had commented on the tilt between COIN and Mr. Walsh, the president of the Chicago National Bank, and claimed that COIN had floored the great financier, in his answer to Mr. Walsh's proposition, that the government could not by legislation add to the commercial value of a commodity.

The Times pronounced the statements of COIN unanswerable and said that interested parties had purposely kicked up a dust about silver, obscured and misrepresented the facts, and when confronted were unable to make good their statements, or answer the arguments of the bimetallists.

All who had been there on the previous days and who came early enough to get in were there, and many new faces could be seen in the audience.

Objection was raised by the audience to free admission. COIN was asked to admit people only on tickets, so seats could be procured, and to charge $2.00 a seat.

This COIN agreed to with the understanding that the proceeds should go to the "soup houses" of Chicago, and this announcement was made just before the lecture for the day began, to take effect the next morning.

COIN had entered by a private door, and just at 10 o'clock came forward on the platform.

A DAY OF QUESTIONS.

He was met with a question at the beginning and it soon developed that it was to be a day of questions.

Professor Laughlin, head of the school of political economy in the Chicago University, an avowed monometallist, whose question had the attention of the whole house, said:

"You have stated since this school began, that so long as free coinage was enjoyed by both metals that the commercial value of silver and gold had never differed more than 2 per cent, and that this difference was accounted for by the disturbance of the French ratio and the cost of exchange. Am I right in so quoting you?"

"You are," replied COIN. "Now, is it not a fact," said the professor, "that several times prior to 1857 silver coin sold at a premium as high as 8 per cent over gold?"

"Yes. That is true," replied COIN.

"Then why did you make the statement you did? And if what you now admit is true, then is there not liable at all times to be a wide margin between gold and silver which free coinage cannot control?"

"Professor," began COIN, with a smile on his handsome, young face, "I hardly think you are serious in asking me that question. We were speaking of silver and gold bullion and not of silver coin. A demand often arises for small money. Suddenly change or small bills are found to be scarce in a large city. This was the case in New York last year, 1893, when silver dollars commanded a premium of 3 per cent not because of the silver being worth more than a dollar but because factories had to have small bills which they could not get to use in paying off their men. They paid the same premium for one and two dollar bills.

"A great inconvenience had arisen for the want of small money, and a premium had to be paid to get it. At the time you speak of, nearly all small money was made from silver, and on account of the French premium for silver our silver was leaving us. Small money was scarce, and frequently commanded a premium, not on account of the value of the silver bullion, but upon the demand for small money. Gold dollars commanded the same premium as silver dollars and fifty-cent pieces.

"If you are not satisfied with my answer I have the exchangeable quotations of silver and gold bullion at the time you speak of."

The professor had taken his seat. He now arose to say that he was satisfied with the answer.

"I am glad these questions are asked," said COIN.

"These statements when used and not answered confuse the people."

THE LATIN UNION.

Mr. J. A. Montgomery, Superintendent of Mails at Chicago, then arose and asked this question:

"What would silver and gold be worth if neither were used as money?"

"That would depend," said the little financier, "on what was adopted as money to take their place and the quantity of it. Primary money becomes the measure of all values; and the value of any other commodity is more or less, as the quantity of primary money is more or less. That is the reason you hear gold referred to now as the standard or measure of values.

"The most impartial way to get at what the value of silver and gold would be if not used as money would be to suppose there was no money of any kind.

"Then there would be no measure of values, and only an exchange value would exist. If under these circumstances the arts and sciences progressed, the demand for silver and gold would cause other property to be exchanged for it, and as they are used in so many ways in the sciences and arts, and for domestic and ornamental purposes, it is reasonable to suppose they would have an exchange value equal to any other scarce property for which there was a demand.

"When it is considered that they are both precious metals - neither found in even or regular veins, and difficult and expensive to mine it is not unreasonable to suppose that great store would be placed upon their possession when refined into the pure metal.

"Brass, copper, and other metals than silver and gold, with anything like their specific gravity, discolor the skin when worn as ornaments.

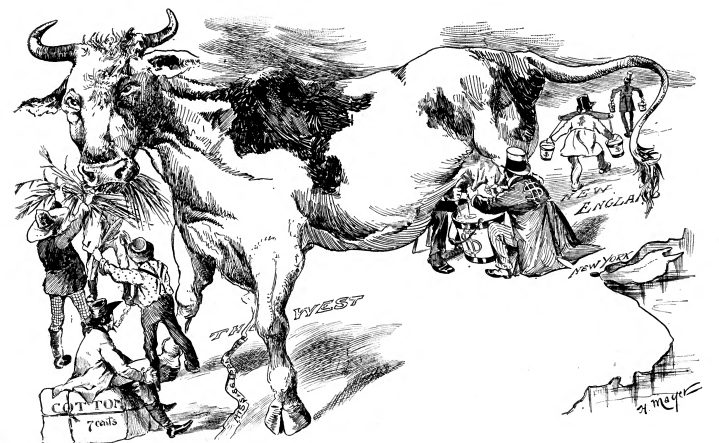

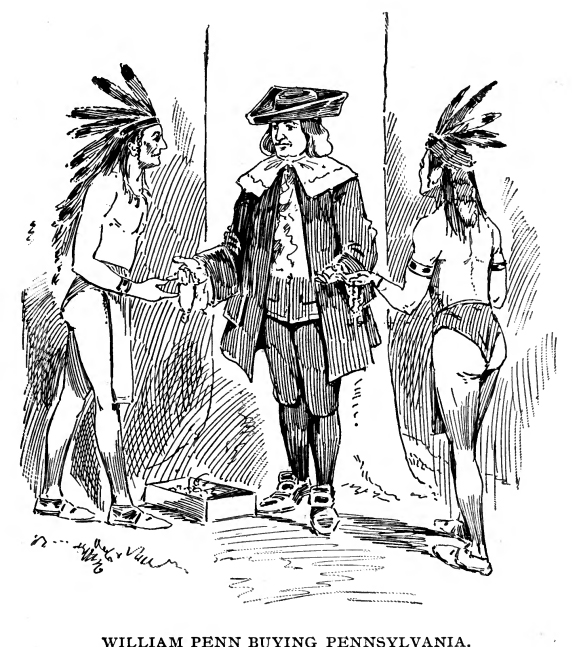

"When we consider that the native Indians of this country were known to give up large quantities of valuable property in exchange for a few trinkets and ornaments, and that large domains of land were purchased in this way, it is natural to believe that a civilized man would give up as much as a bushel of wheat for the amount of silver in one of our silver fifty-cent pieces when fashioned into a ring.

"Cups, pitchers, spoons, table knives, and other forms of table ware made from or plated with silver or gold, will not stain either the liquids or food. Their use in manufacture, chemistry, and some other branches of the arts and sciences are now regarded as indispensable, and more than one-half of the total output of the world is so used.

"It has been said that silver and gold have no intrinsic value; this is not true. They are the only things used by Webster in the copy of his dictionary which I have to illustrate the meaning of the word 'intrinsic.'

"But exchange value, in the sense that a civilized or uncivilized person will barter or trade one property for another, is the primary value of all property.

"Iron cannot be used for food, but its utility gives it an exchange value. Silver can be utilized for many mechanical purposes for which iron serves, and can be adapted to a thousand uses where iron would not be suitable.

"Therefore, what the value of silver and gold would be if not used as money, to be expressed in dollars and cents, would depend, first, on what the new unit or dollar was, and then the abundance of the material from which it was being made; but when established, they would, I think, have a value relatively with other property not much different from what they have had as the world's money."

COST OF PRODUCING SILVER.

Mr. M. L. Scudder, Jr., asked this question:

"Is it not a fact that silver can be mined for fifty cents an ounce, and does not the cost of production regulate its value?"

COIN replied as follows:

"It is not a fact that silver can be mined for fifty cents an ounce. In some particular mine, for a time, it may be mined for fifty cents an ounce, or less; just as gold has been mined for a time in Australia and California for ten per cent of its value."

"You must not judge of the cost of mining precious metals by any one mine; or by mining coal, iron, or other metals and minerals that lay in even veins. The latter class is demonstrated by geological formation and experience to be reliable in quality and quantity; works are erected, and conservative management and business judgement are safely applied to its production.

"Not so with silver and gold mines. They are most unreliable in both quality and quantity. Costly buildings and machinery are often erected to economize the mining of the ore, only to find no mine to operate by the time the buildings are completed and the machinery is working.

"Silver and gold are found in uneven and broken veins and pockets. Sometimes the 'pay streak ' is a foot wide, to narrow down to an inch a few feet farther on. A single blast has been known to 'blow out' a mine - and with it the hopes of those who before the shot was fired thought they were millionaires.

"A silver mine that will assay 100 ounces to the ton at 200 feet depth, has been known to run only 0.10 ounces at 400 feet depth. The Yankee Girl mine in Red Mountain, Colorado, was a heavy dividend payer, at 300 feet, and the ore was too low grade to pay to hoist at 800 feet. The Comstock mines changed at 1,600 feet from high grade to low grade ore. The reverse is just as often true. Mines that are low grade near the surface are high grade with depth.

"It is estimated by all men of judgement who have given practical attention to mining, that the silver now in existence has cost not less than $2.00 per ounce, and many put it much higher.

"Mining for silver and gold has a speculative and gambling feature to it, that will lure men on notwithstanding the great cost, because a few 'strike it rich'; just as men will speculate on the Board of Trade, though in the end ten lose to where one gains. If Mr. Scudder's proposition were true, you would all be engaged in silver mining.

"But your presence here gives me an opportunity to forever set this question at rest. I am sure that in so large an assemblage of wealthy Chicago men, many of you have had some experience in silver mining. Now, if all of you," and COIN began to smile, "who have lost money in mining for silver will rise to your feet, I will then call on those who have made by it to stand up also."

The applause indicated clearly that the young economist had clinched his point; and the smile that went round told that the shot had gone home. Sitting in the assembly were many prominent Chicago citizens who had invested in silver mining and had made a sufficient test to satisfy themselves both as to the risk incurred and the cost per ounce of mining silver.

A GREENBACKER

Mr. E. R. Ridgeley, of Ogden, Utah, who was in the audience, said he would like to ask a question.

"Proceed," said COIN.

"I want to know," said Mr. Ridgeley, "if it is not practical to maintain a purely greenback system."

"Yes," said COIN. "The only theory, however, on which a purely greenback or paper money system might be maintained would be to do away with a redemption money entirely. You cannot have both without the redemption principle applying. The money with a value in itself becomes the most preferable, and must stand behind the other.

"You cannot maintain two kinds of money at a parity, when one has a commercial value and the other has none, except by making one redeemable in the other.

"But you might have a purely paper money. The method would be to have no redemption money and to make it legal tender in the payment of all debts public and private.

"Limit it in quantity by fixing the amount at so much per capita. Maintain the volume at that as population increased, and from time to time provide for what had been destroyed. The fact that it was limited in quantity, and the uses for which it was intended, would give it a value, and make it a measure of values, and a serviceable medium of exchange.

"Silver and gold would be treated as any other merchandise, and would be purchased at their market value, and exported to other countries, where they might be used as money, or for use in this or other countries in the arts and sciences."

"Then," said Mr. Ridgeley, "what objection is there to such a system?"

"The objection which is urged," said COIN, "is this: So long as there was confidence in the government, it would be a sound, stable money. But so soon as confidence in the government was shaken it would depreciate in exchangeable value. When the danger became imminent that the government was not able to enforce its legal tender character, having no commercial value, it would become more or less worthless.

"The paper or substance out of which it is made, would have no exchangeable value, unlike money made from a valuable commodity; when much disturbed a lack of confidence it would fluctuate in value; and if the government went down it would be entirely worthless.

"Money with a commercial value makes a medium of exchange with the balance of the world, and facilitates our trade."

"But," said Mr. Ridgeley, who was still standing: "Isn't it a fact, that when war, and great disturbances come, that redemption money disappears, and paper money takes its place anyhow? So are not the people at such times embarrassed with a paper money fluctuating with their confidence in the government, and saddled with a worthless paper money if the government goes down, and does the use of silver and gold as money ever prevent this condition from arising?"

"If the use of redemption money," replied COIN, "does not prevent the conditions you describe. Paper money always takes its place at such times. The people, however, are not injured by it. They store away their good money and have it in their possession ready to use at any time, and it becomes especially useful if the other money should worthless.

"After the use of redemption money ceases because of war, every one is on the same footing. As the paper money fluctuates from day to day, all are taking chances alike. If it becomes wholly worthless, all have suffered more or less proportionately, and primary money immediately takes its place.

"This latter is true, whether a new government is founded on the ruins of the old one at once or not. There may be a long interregnum, as in France toward the close of the last century, when one form of government was from year to year almost, substituted for another. No one knew what was coming next. No stability was in the government itself. During such a period, which may last for years, it would be impossible to make paper money circulate. But money made from property having a commercial value would circulate, and would assist materially in restoring order and civilization. In fact, it would be hard to restore civilization without its use during such a period.

"We are approaching such a period now, unless wise statesmanship shall intervene; commodity money silver and gold will be our only money, and will have to answer the purpose of a medium of exchange until a stable government can get on its feet and issue paper money.

"All know and feel the necessity of money, and if chaos comes in this country, it may be years before there is another government sufficiently established to give confidence generally to its issue of paper money.

"In the meantime silver and gold coin will be the only thing on which we can rely for money, and of the two silver will face as it always has been, the greatest friend of the people.

MONEY BASED ON LABOR.

J. R. Sovereign, Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, who had a seat on the platform, now asked a question:

"You have given us the theory and science of money," said Mr. Sovereign, "as based on property. I want to know if it is practical to issue a form of credit money based on labor?

"Yes," said COIN. "It is practical, and, to the extent to which it could be brought into use, would be on a parity with other forms of money based on property.

"Suppose the government owned and controlled all the railroads it could issue paper money redeemable in services. That is, it would be good in the payment of freight and at all the ticket offices.

"If the passenger and freight business of the country amounted to $1 - 100,000,000 a year, which is the case at present, then that amount of paper currency thus redeemable could be safely kept in circulation. The supply would have to be limited so that confidence would be maintained in the ability of the government to redeem it, in a reasonable time, if called upon so to do.

"This would be credit money redeemable in labor. It should also be made legal tender, and differ in no respect from credit money redeemable in property silver and gold except as to the nature of redemption.

"Naturally it would circulate side by side with the other form of credit money, inside of the United States, and in the payment of freight and purchase of transportation, no discrimination would ordinarily be made in the form of money used.

"If confidence in the existence of the government should be shaken by wars or disintegration, as such a danger arose, this form of money would be assorted out from the other and redemption could take place, and no one would suffer by it.

"It would be as sound a currency as credit money based, on property.

"It would be put in circulation by the government paying it out to its employees.

"The postage stamp is based on the principle of redemption in services, but is not issued in suitable form for currency, and yet it is frequently used in small remittances in letters as such.

"A form of credit money could now be issued resembling our paper bills, redeemable in postage stamps."

"How much?" asked Mr. Sovereign, whose face had worn a broad smile during the answer to his previous question.

"The total annual postal business," said COIN, "of the government for last year was about $75,000,000. This amount would circulate at par, with other money how much more I would not now undertake to say. It would be redeemable in postage stamps, just as the other would be redeemable in railroad passenger tickets, or receipted freight bills.

"This would be money based on labor."

NO SPECIAL ADVANTAGE TO SILVER STATES.

COIN was here interrupted by President Struckman, of the Board of County Commissioners, who said:

"Is it not unfair to give the owners of silver bullion the special privilege of having the value of their property enhanced? Is it not virtually making a present of millions of dollars to the owners of silver bullion by remonetizing silver? Is this just or right?"

"In the first place," replied COIN, "whatever you select as primary money should be treated distinctively different from all other property. It should not be left on the market to be bulled or beared. Otherwise you cannot have a stable money.

"Free coinage at a fixed quantity to constitute a dollar does take it off the market, and that is what is necessary in the treatment of a money metal. That is the way gold is now treated, and silver should be so treated.

"But your statement is not true. Silver men are not benefited by remonetization except in common with others. Silver is now worth about 60 cents an ounce as measured in the new standard gold. It was worth $1.29 per ounce under free coinage. The owner of silver bullion can now buy as much with an ounce of silver as he ever could.

"An ounce of silver bullion would buy a bushel of wheat in 1873, and it will buy a bushel of wheat now. Two ounces of silver bullion would buy a day's labor in 1873, and two ounces will buy a day's labor now. Three ounces of silver bullion would buy a keg of nails in 1873, and two ounces will buy a keg of nails now. An ounce of silver bullion would buy 16 yards of calico in 1873, and it will buy 1.6 yards of calico now.

"The exchange value of uncoined silver with the other products is substantially the same now as it ever was. Where silver producers are hurt is only in common with all producers stagnation, falling prices, paralysis of business, and confiscation of property by taxation and debts that do not shrink with all other values."

COIN'S answer was satisfactory. This was evident not from applause, for there was none; but from the intense stillness and breathless attention. It was also attested from the further fact that there sat in the audience men ready to leap upon him at the least show. His answers had to be absolutely convincing, or an antagonist was there ready to puncture the weak places. Not one opened his mouth. COIN was like a little monitor in the midst of a fleet of wooden ships. His shots went through and silenced all opposition.

PROFESSORS OF POLITICAL ECONOMY.

There was Professor Laughlin still irritated at his unsuccessful attack on the little bimetallist. As the professor in a chair of political economy, endowed with the money of bankers, his mental faculties had trained with his salary, but his views had been those of theory. Those views now encountered the practical statesman. He moved nervously in his chair, but said nothing.

Here was a study and an object-lesson. Combined capital all over the world had been using professors of political economy to instruct the minds of young men to a belief in the gold standard. This is not hard to do, as these students, being young, their minds are easily molded. The error is planted deep and strong.

Anything can be proved by theoretical reasoning. In the practical application of a theory is the proof of its strength. The gold standard, now fitted to a shivering world, is squeezing the life out of it. The men of the country, the backbone of the republic, on whose strong arms the life of the nation may depend, are delivering over their property to their creditors, and going into beggary. This is the test proof of the beneficence of monometallism.

There sat a representative professor on political economy, at home when with his school boys, but powerless and confused in the presence of an adversary who courted his questions, but which he knew it was useless to propound.

"You do not enrich the people of the silver states one cent by the remonetization of silver," continued COIN, "except in common with the people of the state of Illinois, and of the whole United States.

"You increase the value of all property by adding to the number of money units in the land. You make it possible for the debtor to pay his debts; business to start anew, and revivify all the industries of the country, which must remain paralyzed so long as silver as well as all other property is measured by a gold standard."

Mr. Struckman interrupted COIN to say, that the answer to his proposition was entirely satisfactory. That the reply given had never occurred to him, simple as it was. That he wanted to say further, he considered that the people of Chicago had been imposed on by some of their great newspapers; what private object they had, or whose interests they were serving, he did not know; but they had misrepresented the silver question. He felt better to make this open confession, and he thought other gold-bugs would feel better if they would do likewise.

IMPROVED FACILITIES.

Mr. Kirk, President of the American Exchange National Bank, was now seen standing up, and COIN stopped to hear the question he was about to put.

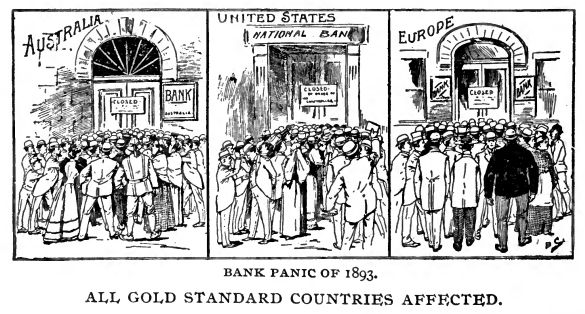

"Have not the improved facilities for production," asked Mr. Kirk, "caused a general lowering of prices, and is not this mainly responsible for the gradual decline since 1873?"

COIN replied: "Improved facilities for production have not been continuous when applied to any one article in the sense of explaining the decline in prices.

"Nearly everything except gold has declined largely in the last two years - the average is about twenty-five per cent - and it may be said that little or no improved facilities have come into use during that time. Demonetization and the collapse of our financial system seems to have paralyzed the hand of even the inventor, and yet values continue to decline.

"Improved facilities as a rule do have a tendency to lower prices, but it is only an incident, and not the cause of the overthrow of our industries.

"When the demand is greater than the supply, prices may advance at the very time that improved facilities for production are in progress.

"Improved facilities for mining gold, both in the placer and quartz mines, are continuously being applied; and yet the value of that metal, in purchasing power, is continuously rising.

"Take the case of wool. There has been no improved facilities for making it grow on the backs of sheep, or of shearing them, in the last twenty years, and yet wool is only about one-third the price it was a few years ago. It, with many other articles that can be put in the same class, have been steadily declining in price as expressed in terms of dollars and cents.

"A gentleman from Oregon, now in the audience, tells me that he has lately seen horses in his state sell at auction for 75 cents each. And that horses in droves have been offered there recently at one cent a pound at private sale, with no one willing to take them. It can not be said, that there are any improved facilities, for raising horses."

THE TARIFF PROPOSITION.

Mr. H. H. Kohlsaat, late proprietor of the Inter Ocean, now said that he wanted to say something, and as he had COIN'S attention, immediately proceeded to state the tariff proposition. Mr. Kohlsaat claimed that the threat to reduce or abolish tariff, in his opinion, had more to do with the hard times than anything else. That since attending these lectures he had more than ever recognized the damage demonetization had done; but he still thought the tariff an important question.

In replying COIN admitted that a large business interest was more or less disturbed when it was proposed to change the tariff schedule. With manufacturers it was not so much a question of how much the tariff is, as what it is, and so long as that was in doubt it was a disturbing element.

"But," said COIN, "we are trying to get at what is the main or underlying cause of our present industrial demoralization, and tariff, pro or con, will not account for it. Our decline in values has been going on steadily and persistently since the demonetization of silver. During that period we have had different tariff bills, and of late years a very high tariff schedule, and yet it has had no effect in stopping the fall of prices.

"What more clearly than anything else demonstrates that tariff is not the trouble we are searching out, is that the same business depression existing in the United States also prevails in Europe, Australia, and all countries where gold has been made the standard and measure of values. "To see only our own trouble, and attribute it to local causes, is to be like the narrow-minded Chicago man who attributes the present depression, to the World's Fair.

"The Chicago Post published the following the other day from the San Francisco Chronicle, that will forcibly illustrate my answer to this question;" and COIN read the following:

"The San Francisco Chronicle, says advices from Australia by the steamer Warrimoo show an alarming increase in casualties, crimes and acute distress. The police are unable to cope with desperate housebreakers, who swarm in the large cities. A few that have been arrested give as an excuse that famine drove them to deeds of violence. Several of the policemen attacked by burglars at Sydney are dying. The survivors have been promoted and given bonuses by Sir George Gibbs. On one day last week at Sydney, besides a score of petty robberies, the City Hospital was robbed of all its valuables by nurses; Mercredie & Drew, manufacturers, were robbed of fifty thousand dollars by employees; F. Coxon, merchant, was robbed by an employee of a large sum. Three young women succeeded in passing a number of counterfeit checks. Charles Graham, a post office clerk, embezzled two hundred dollars from the post office.

The government's claim is that the unemployed problem is too complicated to solve. In Sydney five hundred dollars each week is spent in aiding five hundred families. Five thousand men in South Australia asked the Governor to call a special session of Parliament to discuss means to aid them. The Governor refused. Then they waited on Premier Kingston, but the Premier would promise nothing. He told them that though they were in want of food, they had refused to break a yard and a half of rock per week for rations, and he could do no more. The delegation said that they would not break rock for food alone.

Thousands are sleeping in the open air and several have starved to death. At Bourke Afghans and Europeans quarrelled over a division of labor, and a bloody row occurred. The most tragic suicides out of ninety-eight in one week, directly the result of hard times, are: F. W. Wilson, the biscuit manufacturer of Brisbane, shot himself; William O'Connor, lodger in the European Hotel, Melbourne, jumped from the fourth story and dashed his brains out on the pavement; Kate Brooks, a pretty English girl, starving, got drunk and killed herself with poison; Joseph Bancroft, a miner, out of work, said good-bye to his family and exploded a cartridge in his mouth.

As COIN closed the reading of the extract from the San Francisco Chronicle, Mr. Joel Bigelow asked him to read an extract from a paper published in London called "The Colonies and India" which Mr. Bigelow then had in his hand. COIN consenting, Mr. Bigelow came forward with the paper, and COIN read the extract as follows:

One of our contemporaries asks: "What is the most constant standard of value in existence?" There can be but one rational answer, in fact - viz., silver. The value of a ton weight of silver on any given day - whether expressed in £. s. d. in dollars and cents, in francs, in marks, or in rupees and pice, and (compared on the same day with) the sum of the market prices of standard test quantities of each of one hundred varieties of the most generally-dealt-in commodities of the market, also expressed in the same money terms have by statistical observation and many hundreds of official tests, practically been found the constant equivalent, on the same market, of each other during the last five and twenty years since the system of "index numbers" was invented and applied to this branch of national business. This fact stands officially recorded. For Great Britain the Board of Trade publishes tables which prove it, and such, or their own private statistics, are regularly printed in leading commercial journals.

Continental scientists also regularly publish their independent statements of these "index numbers." The truly marvelous fact above stated is thus capable of absolute verification by each one for himself, and if this does not prove silver to be the true and world-wide standard of value then there is no significance in facts. The metal gold, on the contrary, tried by the same supreme test, shows itself to be in no sense a "standard" of value, for it jumps about like the mercury in a barometer with every movement of the commercial atmosphere, its vibrations to speak within the fact having dodged about, up and down, as much as 20 per cent, down from a given point and then back to that point, and then 20 per cent, up from that same point, all within the short space of 40 or 50 years! How in the name of commercial sanity, how with a profession of national honesty, how with a claim to the meanest common sense, the Government of England continues to oppose the restoration of our ancient, proved, and only honest standard of value passes the wit of sane onlookers to understand.

MAYOR HOPKINS ASKS A QUESTION.

Mayor Hopkins wanted to know what effect the adoption of the gold standard by the governments using it had, if any, on those nations using a silver or bimetallic standard. What effect, if any, it had on their prosperity?

COIN'S reply was: "If a bimetallic or silver standard nation, or its people, are largely in debt, with the obligations payable in gold, the effect is serious. Take our South American republics to illustrate it: During the last 30 years they have been getting deeper and deeper into debt to England, and during the last 25 years these debts have been made payable in gold.

"Each year, with the advance in gold it takes more and more of their products, or silver, to pay the gold bonds; they must give up in silver $1.25 to pay $1 in gold - $1.50 in silver to pay $1 in gold - $1.75 in silver to pay $1 in gold, and so on, as the purchasing power of gold advances; and at the present time $2 in silver to pay $1 in gold. So that a bond for $100,000 executed by them when silver and gold were at a parity, payable in gold, must now be met by the payment in principal of $200,000 in their money. That is - to raise the $100,000 in gold, they must sell 200,000 of their silver dollars. You will notice in the London Financial reports the price of Mexican dollars as 50 cents or 49 cents as the case may be; which means that about two Mexican silver dollars are accepted in payment for one dollar in gold settlements.

"The bonds of these countries both national and private are held in England for large amounts, and the enhanced value of gold is having a very serious effect on their prosperity. We are now an ally of England in depressing the price of silver and enhancing the value of gold.

"We are paying England 200 million dollars annually in gold in the payment of interest on our bonds, national and private, owned by her people, and to meet this annual interest we are giving up about 400 million dollars in property that is required in the market to secure the 200 million in gold.

"Our silver dollars are at par with gold by reason only of our enforcement of the gold standard redeeming silver with gold. Otherwise we are with reference to debts in the same fix as our Southern neighbors, with this difference; while they settle their foreign debts only in gold, we settle both foreign and domestic debts on the gold basis, and in each instance part with about two portion of property in settlement for one portion of debt."

And with this COIN announced the close of the lecture for the day. As he did so Mr. Stone, secretary of the Chicago Board of Trade, stood up in his chair in the "CENTER" of the hall, and addressing COIN, said:

"The members of the Board of Trade would like to attend tomorrow's lecture, but the regular session of the board lasts till 1p.m.; if it could be arranged to have the 'school' open at 2 p.m. instead of 10 a.m., it would make it possible for us to be present. And in that event I am commissioned to buy three hundred tickets for tomorrow's lecture. We feel a special interest in what shall take place here tomorrow, as I am creditably informed the price of wheat will be discussed."

COIN consented to the request made by Mr. Stone, and the time for opening the school on the next day, Friday, was set for 2 p.m. Mr. H. M. Millliken, a young bimetallist was selected by COIN as manager and treasurer of the hall under the new system adopted of charging for seats. Mr. Stone at once selected and paid for three hundred seats, to be occupied by members of the Board of Trade.