Matrix Files

Where You Have Taken The Red Pill

Coin's Financial Course - Chapter I

« Preface PDF File found here Chapter 2 »

CHAPTER I.

So much uncertainty prevailing about the many facts connected with the monetary question, very few are able to intelligently understand the subject.

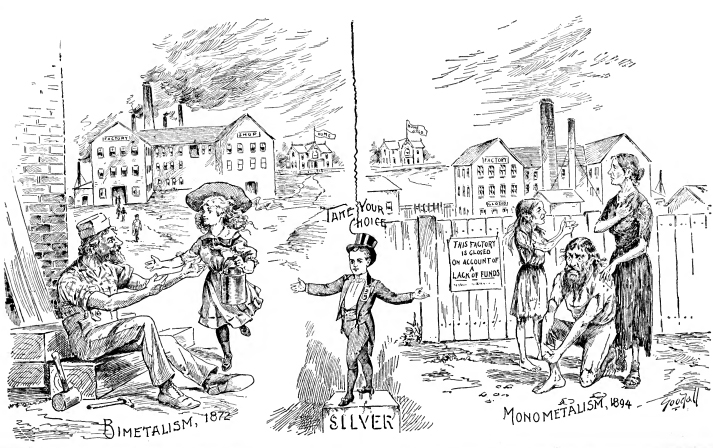

Hard times are with us; the country is distracted; very few things are marketable at a price above the cost of production; tens of thousands are out of employment; the jails, penitentiaries, workhouses and insane asylums are full; the gold reserve at Washington is sinking; the government is running at a loss with a deficit in every department; a huge debt hangs like an appalling cloud over the country; taxes have assumed the importance of a mortgage, and 50 per cent of the public revenues are likely to go delinquent; hungered and half-starved men are banding into armies and marching toward Washington; the cry of distress is heard on every hand; business is paralyzed; commerce is at a standstill; riots and strikes prevail throughout the land; schemes to remedy our ills when put into execution are smashed like box-cars in a railroad wreck, and Wall street looks in vain for an excuse to account for the failure of prosperity to return since the repeal of the silver purchase act.

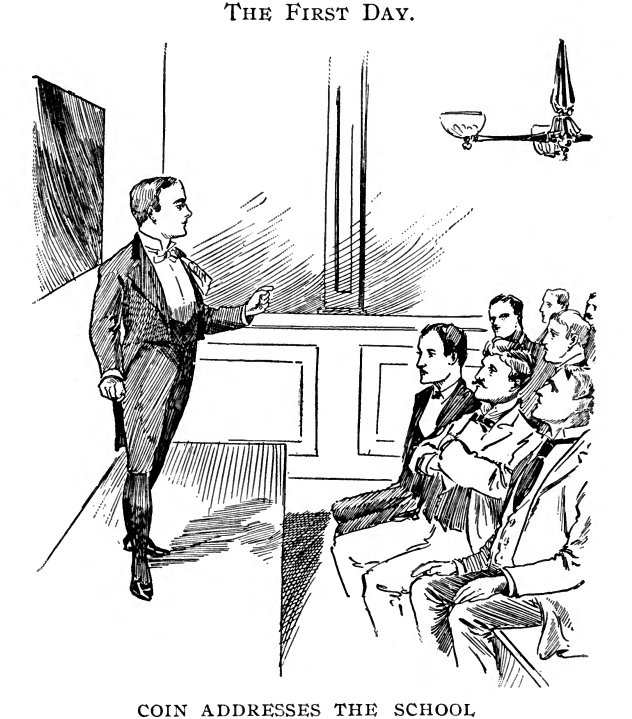

It is a time for wisdom and sound sense to take the helm, and COIN, a young financier living in Chicago, acting upon such a suggestion, established a school of finance to instruct the youths of the nation, with a view to their having a clear understanding of what has been considered an abstruse subject; to lead them out of the labyrinth of falsehoods, heresies and isms that distract the country.

The school opened on the 7th day of May, 1894.

There was a good attendance, and the large hall selected in the Art Institute was comfortably full. Sons of merchants and bankers, in fact all classes of business, were well represented. Journalists, however, predominated. COIN stepped on to the platform, looking the smooth little financier that he is, and said:

"I am pleased to see such a large attendance. It indicates a desire to learn and master a subject that has baffled your fathers. The reins of the government will soon be placed in your hands, and its future will be molded by your honesty and intelligence.

"I ask you to accept nothing from me that does not stand the analysis of reason; that you will freely ask questions and pass criticisms, and if there is any one present who believes that all who differ from him are lunatics and fools, he is requested to vacate his seat and leave the room."

The son of Editor Scott, of the Chicago Herald, here arose and walked out. COIN paused a moment, and then continued: "My object will be to teach you the A, B, C of the questions about money that are now a matter of every-day conversation.

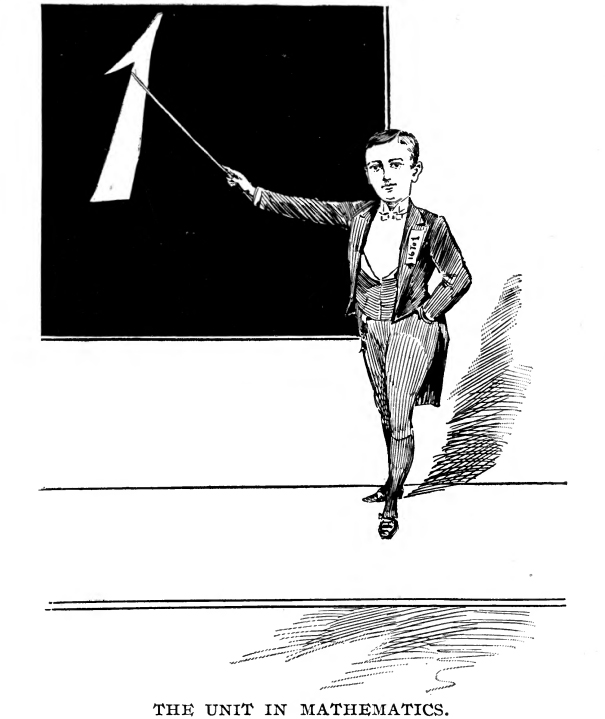

THE MONEY UNIT.

In money there must be a unit. In arithmetic, as you are aware, you are taught what a unit is. Thus, I make here on the blackboard the figure 1. That, in arithmetic, is a unit. All countings are sums or multiples of that unit. A unit, therefore, in mathematics, was a necessity as a basis to start from. In making money it was equally as necessary to establish a unit. The constitution gave the power to Congress to 'coin money and regulate the value thereof.' Congress adopted silver and gold as money. It then proceeded to fix the unit.

"That is, it then fixed what should constitute one dollar, the same thing that the mathematician did when he fixed one figure from which all others should be counted.

Congress fixed the monetary unit to consist of 371¼ grains of pure silver, and provided for a certain amount of alloy (baser metals) to be mixed with it to give it greater hardness and durability. This was in 1792, in the days of Washington and Jefferson and our revolutionary forefathers, who had a hatred of England, and an intimate knowledge of her designs on this country.

"They had fought eight long years for their independence from British domination in this country, and when they had seen the last red-coat leave our shores, they settled down to establish a permanent government, and among the first things they did was to make 371¼ grains of silver the unit of values. That much silver was to constitute a dollar. And each dollar was a unit. They then provided for all other money to be counted from this unit of a silver dollar. Hence, dimes, quarters and half-dollars were exact fractional parts of the dollar so fixed.

"Gold was made money, but its value was counted from these silver units or dollars. The ratio between silver and gold was fixed at 15 to 1, and afterward at 16 to 1. So that in making gold coins their relative weight was regulated by this ratio.

"This continued to be the law up to 1873. During that long period, the unit of values was never changed and always contained 371¼ grains of pure silver. While that was the law it was impossible for any one to say that the silver in a silver dollar was only worth 47 cents, or any other number of cents less than 100 cents, or a dollar. For it was itself the unit of values. While that was the law it would have been as absurd to say that the silver in a silver dollar was only worth 47 cents, as it would be to say that this figure 1 which I have on the blackboard is only forty-seven one-hundredths of one.

"When the ratio was changed from 15 to 1 to 16 to 1 the silver dollar or unit was left the same size and the gold dollar was made smaller. The latter was changed from 24.7 grains to 23.2 grains pure gold, thus making it smaller. This occurred in 1834. The silver dollar still remained the unit and continued so until 1873.

"Both were legal tender in the payment of all debts, and the mints were open to the coinage of all that came. So that up to 1873, we were on what was known as a bimetallic basis, but what was in fact a silver basis, with gold as a companion metal enjoying the same privileges as silver, except that silver fixed the unit, and the value of gold was regulated by it. This was bimetallism. "Our forefathers showed much wisdom in selecting silver, of the two metals, out of which to make the unit. Much depended on this decision. For the one selected to represent the unit would thereafter be unchangeable in value. That is, the metal in it could never be worth less than a dollar, for it would be the unit of value itself. The demand for silver in the arts or for money by other nations might make the quantity of silver in a silver dollar sell for more than a dollar, but it could never be worth less than a dollar. Less than itself.

"In considering which of these two metals they would thus favor by making it the unit, they were led to adopt silver because it was the most reliable. It was the most favored as money by the people. It was scattered among all the people. Men having a design to injure business by making money scarce, could not so easily get hold of all the silver and hide it away, as they could gold. This was the principal reason that led them to the conclusion to select silver, the more stable of the two metals, upon which to fix the unit. It was so much handled by the people and preferred by them, that it was called the people's money.

quot;Gold was considered the money of the rich. It was owned principally by that class of people, and the poor people seldom handled it, and the very poor people seldom ever saw any of it."

THE FIRST INTERRUPTION.

Chicago Tribune, held up his hand, which indicated that he had something to say or wished to ask a question. COIN paused and asked him what he wanted. He arose in his seat and said that his father claimed that we had been on a gold basis ever since 1837, that prior to 1873 there never had been but eight million dollars of silver coined. Here young Wilson, of the Farm, Field and Fireside, said he wanted to ask, who owns the Chicago Tribune?

COIN tapped the little bell on the table to restore order, and ruled the last question out, as there was one already before the house by Mr. Medill.

"Prior to 1873," said COIN, "there were one hundred and five millions of silver coined by the United States and eight million of this was in silver dollars. When your father said that 'only eight million dollars in silver had been coined, he meant to say that 'only eight million silver dollars had been coined.' He also neglected to say - that is - he forgot to state, that ninety-seven millions had been coined into dimes, quarters and halves.

"About one hundred millions of foreign silver had found its way into this country prior to 1860. It was principally Spanish, Mexican and Canadian coin. It had all been made legal tender in the United States by act of Congress. We needed more silver than we had, and Congress passed laws making all foreign silver coins legal tender in this country. I will read you one of these laws they are scattered all through the statutes prior to 1873." Here COIN picked up a copy of the laws of the United States relating to loans and the currency, coinage and banking, published at Washington. He said: "A copy could be obtained by any one on writing to the Treasury Department."

He then read from page 240, as follows: "And be it further enacted, that from and after the passage of this act, the following foreign silver coins shall pass current as money within the United States, and be receivable by tale, for the payment of all debts and demands, at the rates following, that is to say: the Spanish pillar dollars, and the dollars of Mexico, Peru and Bolivia, etc. * * * * *

"On account of the scarcity of silver, both Jefferson and Jackson recommended that dimes, quarters and halves would serve the people better than dollars, until more silver bullion could be obtained. This was the reason why only about eight million of the one hundred and five million of silver were coined into dollars.

"During this struggle to get more silver," continued COIN, "France made a bid for it by establishing a ratio of 15½ to 1, and as our ratio was 16 to 1, this made silver in France worth $1.03 1/8 when exchanged for gold, and as gold would answer the same purpose as silver for money, it was found that our silver was leaving us. So Congress in 1853, had our fractional silver coins made of light weight to prevent their being exported.

"So that we had prior to 1873 one hundred and five millions of silver coined by us, and about one hundred million of foreign silver coin, or about two hundred and five million dollars in silver in the United States, and were doing all we could to get more and to hold on to what we had. Thus silver and gold were the measure of values. It should be remembered that no silver or gold was in circulation between 1860 and 1873. Two hundred and five millions were in circulation before 1861."

Then looking at young Medill, COIN asked him if he had answered his question. The young journalist turned red in the face and hung his head, while young Wilson muttered something about Englishmen owning the Tribune.

YOUNG SCOTT RETURNS.

Young Scott was seen entering the room; he was carrying in his hand a book. He stopped and addressed COIN, saying that he wished to apologize for his conduct, and was now here to stay if permitted to do so.

COIN told him that so long as he accorded to others the right to entertain views different from his, his name would be kept on the roll as a student at the "Financial School."

Thereupon Mr. Scott said: "I am informed that you have stated that silver was the unit of value prior to 1873; that this unit was composed of 371¼ grains of pure silver or 412 grains of standard silver. Now I want to know if it is not a fact that both gold and silver at that time were each the unit in its own measurement? And that we had a double measurement of values, which was liable to separate and part company at any time? And when the metals did separate, was not the effect like having two yard-sticks of different lengths? I wish to call your attention to the statute on page 213 of the book you read from where it says an eagle or ten-dollar gold piece is ten units. Does not this indicate positively that a gold unit was also provided for?" And with this he sat down looking as proud as a cannoneer who has just fired a shot that has had deadly effect in the enemy's ranks.

COIN had nodded when the proposition of the unit was stated; looked amused at the double unit proposition advanced, and now replied: "The law I referred to this morning was passed April 2, 1792, and remained the law till 1873. You will find it in my valuable Handbook. I now read it from the United States Statutes: "Dollars or units, each to be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four-sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver.

"If you omit the words referring to the Spanish milled dollar, it will then read: "Dollars or units, each to contain 371 grains and 4-16 parts of a grain of pure silver."

"This is the statute that fixed the unit and is the only statute on the subject till we come to 1873.

"Now, what you referred to is this. It is in section 9, and reads as follows:

"Eagles each to be of the value of ten dollars or units."

"And on the ratio of 15 to 1, fixed in the same act, this made an eagle contain 247 grains of pure gold, or 270 grains of standard gold. You will observe that the law does not say, as you stated, that an 'Eagle or ten-dollar gold piece is ten units.' It says: 'Of the value of ten dollars or units.' In other words, a ten-dollar gold piece shall be of the value of ten silver dollars.

"Or to state it in another way: As the law fixed 371¼ grains of pure silver as a unit, the quantity of gold in a gold dollar would be regulated by the ratio fixed from time to time.

"Now," addressing Mr. Scott, "if I have not read your law right, I want you to say so. This is the place to settle all questions of fact. Your law does not say a gold piece has so many units in it, but instead of that, it does say, the gold pieces are to be of the value of so many units."

The young journalist from Washington street had not seen the distinction, and had jumped at conclusions.

When he did see the hole he was in, he leaned over to Evans of the Economist, who sat next to him, and asked him to help him out. Evans thought he had mastered the subject of political economy several years ago, and had named his paper "The Economist." He found now, that he had not gone very deep into the subject. His text-books had been the Tribune, Herald, Recordand Journal. He did not know that they, too, were getting their information in about the same way.

So now when his friend Scott was in trouble, he greatly sympathized with him. But he could not help him, and was seen to shake his head. Scott sat silently in his seat.

"You will observe," continued COIN, "that the law in fixing a dollar or unit does not say, as in the case of gold, that it shall be of the value of 371¼ grains of silver, but that the dollar or unit was silverand its quantity should be 371¼ grains. The amount of alloy added to this quantity of pure silver was afterward changed, but this amount of pure silver, 371¼ grains, has always remained the same and was the unit of values until 1873."

A bright looking kid was now seen standing on a chair in the back part of the room holding up his hand and cracking his finger and thumb. He was asked what he wanted and said: "I want to know what is meant by standard silver?"

COIN then explained that this meant with the government a standard rule for mixing alloy with silver and gold. And when so mixed is called standard silver or standard gold. Before it is mixed with the alloy it is called pure silver or pure gold. The standard of both gold and silver is such that by 1,000 parts by weight, 900 shall be of pure metal, and 100 of alloy. The alloy of silver coins is copper. In gold coins it is copper and silver, but the silver shall in no case exceed one-tenth of the whole alloy. Standard silver and standard gold is the metal when mixed with its alloy.

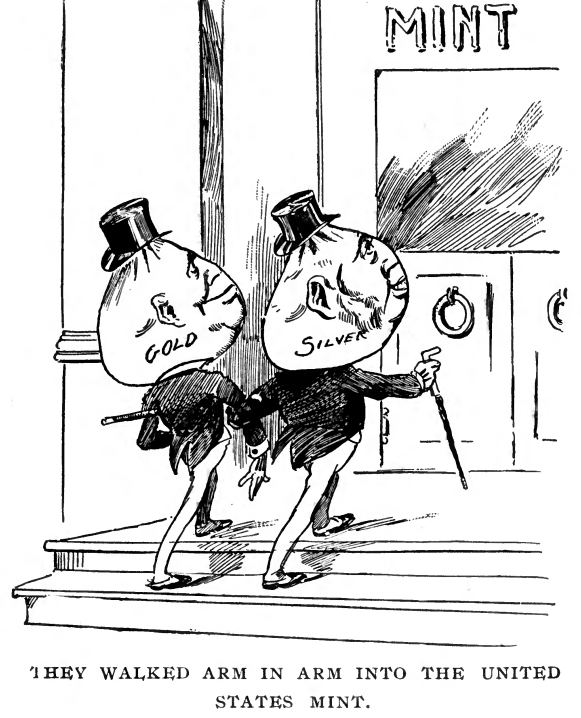

"I now think we understand," said COIN, "what the unit of value was prior to 1873. We had the silver dollar as the unit. And we had both gold and silver as money walking arm in arm into the United States mints.

THE CRIME OF 1873.

"We now come to the act of 1873," continued COIN.

On February 12, 1873, Congress passed an act purporting to be a revision of the coinage laws. This law covers 15 pages of our statutes. It repealed the unit clause in the law of 1792, and in its place substituted a law in the following language:

"That the gold coins of the United States shall be a one-dollar piece which at the standard weight of twenty-five and eight-tenths grains shall be the unit of value.

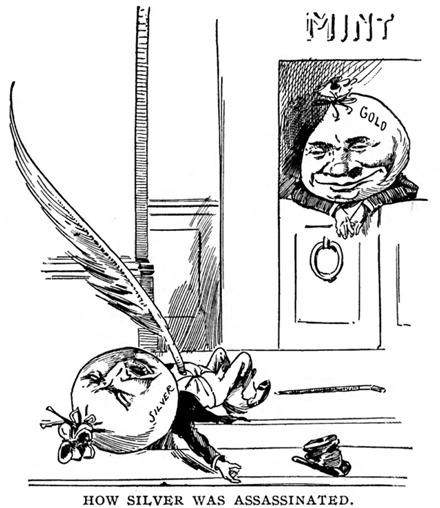

"It then deprived silver of its right to unrestricted free coinage, and destroyed it as legal tender money in the payment of debts, except to the amount of five dollars.

"At that time we were all using paper money. No one was handling silver and gold coins. It was when specie payments were about to be resumed that the country appeared to realize what had been done. The newspapers on the morning of February 13, 1873, and at no time in the vicinity of that period, had any account of the change. General Grant, who was President of the United States at that time, said afterwards, that he had no idea of it, and would not have signed the bill if he had known that it demonetized silver.

"In the language of Senator Daniel of Virginia, it seems to have gone through Congress 'like the silent tread of a cat."

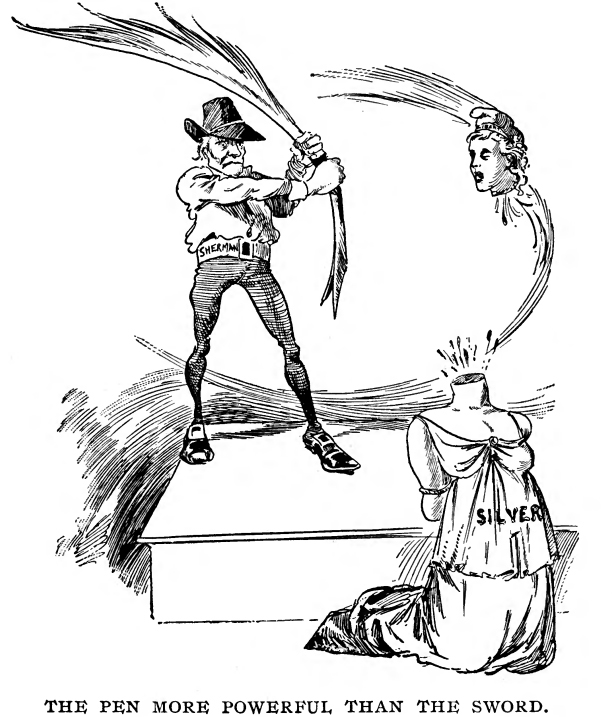

"An army of a half million of men invading our shores, the warships of the world bombarding our coasts, could not have made us surrender the money of the people and substitute in its place the money of the rich. A few words embraced in fifteen pages of statutes put through Congress in the rush of bills did it. The pen was mightier than the sword.

"But we are not here to deal with sentiment. We are here to learn facts. Plain, blunt facts.

"The law of 1873 made gold the unit of values. And that is the law today. When silver was the unit of value, gold enjoyed free coinage, and was legal tender in the payment of all debts. Now things have changed. Gold is the unit and silver does not enjoy free coinage. It is refused at the mints.

"We might get along with gold as the unit, if silver enjoyed the same right gold did prior to 1873. But that right is now denied to silver. When silver was the unit, the unlimited demand for gold to coin into money, made the demand as great as the supply, and this held up the value of gold bullion."

Here Victor F. Lawson, Jr., of the Chicago Evening News, interrupted the little financier with the statement that his paper, the News, had stated time and again that silver had become so plentiful it had ceased to be a precious metal. And that this statement believed by him to be a fact had more to do with his prejudice to silver than anything else. And he would like to know if that was not a fact?

"There is no truth in the statement," replied COIN. "On page 21 of my Handbook you will find a table on this subject, compiled by Mulhall, the London statistician. It gives the quantity of gold and silver in the world both coined and uncoined at six periods at the years 1600, 1700, 1800, 1848, 1880, and 1890. It shows that in 1600 there were 27 tons of silver to one ton of gold. In 1700, 34 tons of silver to one ton of gold. In 1800, 32 tons of silver to one ton of gold. In 1848, 31 tons of silver to one ton of gold. In 1880, 18 tons of silver to one ton of gold. In 1890, 18 tons of silver to one ton of gold.

"The United States is producing more silver than it ever did, or was until recently. But the balance of the world is producing much less. They are fixing the price on our silver and taking it away from us, at their price. The report of the Director of the Mint, published the other day, shows the world's production of precious metals last year was gold, $167,917,337; silver, $143,096,239. So you see the facts are just the opposite of what you had supposed. Instead of becoming more plentiful, it is less plentiful.

"Any one can get the official statistics by writing to the treasurer at Washington, and asking for his official book of statistics. Also write to the Director of the Mint and ask him for his report. If you get no answer write to your Congressman. These books are furnished free and you will get them.

"At the time the United States demonetized silver in February, 1873, silver as measured in gold was worth $1.02. The argument of depreciated silver could not then be made. Not one of the arguments that are now made against silver was then possible. They are all the bastard children of the crime of 1873.

"It was demonetized secretly, and since then a powerful money trust has used deception and misrepresentations that have led tens of thousands of honest minds astray."

William Henry Smith, Jr., of the Associated Press, wanted to know if the size of the gold dollar was ever changed more than the one time mentioned by COIN, viz., in 1834.

"Yes," said COIN. "In 1837 it was changed from 23.2 to 23.22. This change of 2/100 was for convenience in calculation, but the change was made in the gold coin never in the silver dollar (the unit) till 1873."

Adjourned.